According to the US Administration, the nuclear deal between Iran and the six world powers (the UN Security Council’s permanent members plus Germany) “will verifiably prevent Iran from acquiring a nuclear weapon and ensure that Iran’s nuclear program will be exclusively peaceful going forward”. What are the possible implications for Israel, the country that spearheaded opposition to Iran’s nuclear program?

In recent years, top politicians, defense specialists and large parts of the public in Israel have all voiced concern over Iran’s threat to Israel’s national security, some even deeming it existential. While political and defense elites agree that the threat is real, they differ over its nature and over the appropriate response. Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu and Defense Minister Ehud Barak reportedly favored military action – attacking Iran’s nuclear facilities like Israel did in in Iraq in 1981 and, apparently, in Syria in 2007. However, Mossad chief Meir Dagan, Shin Bet (ISA) chief Yuval Diskin and various senior military commanders favored the diplomatic path, i.e. using assertive international policy to prevent Iran from achieving nuclear weapons.

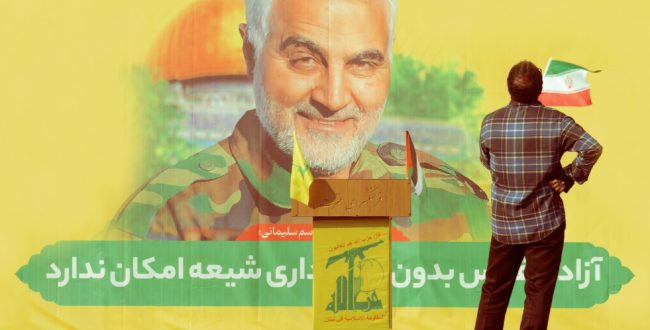

It is important to remember that, although exaggerated at times, the Iranian threat to Israel has not been entirely fabricated. Over the last few decades, Iran stepped up its involvement in Lebanon, primarily by arming the Shi’ite party-militia Hizbullah with thousands of rockets and other weapons for possible use against Israel. Tehran also lent political and military support to Palestinian armed factions such as Hamas and Islamic Jihad – stringent objectors to the PLO and to the Israeli-Palestinian peace process. Iran offered similar support to Syria, Israel’s longstanding enemy, playing a military role in the civil war that has raged there since 2011. Iran’s leadership even directly threatened Israel, stating that it would soon disappear off the map. In other words, Iran has revealed itself – at times explicitly – as Israel’s chief rival in the Middle East. That is how many Israeli policy makers perceive it.

Still, the tendency of Israel’s leaders to present the Iranian threat to Israel as “existential” is unjustified. First, after 67 years of independence, Israel’s existence is no longer at stake. Second, Israel’s relations with its Arab neighbors are highly complex and cannot be viewed only through the Iranian “lens”. Third, Iran, which has close ties with the large Shi‘i communities in Lebanon and Iraq, but also elsewhere in the Middle East (e.g. in the Gulf States), could be expected to foster closer ties with these groups. Lastly, at least some of the steps taken by Tehran in the area of security, including in the nuclear realm were, or so it seems, defensive in nature, and had little to do with Israel.

In 2002, after the US labeled Iraq, Iran and North Korea as part of an “Axis of Evil,” reminiscent of the axis powers in World War II, and in 2003, following the US-led invasion of Iraq, which trampled the latter’s sovereignty, it was not at all surprising that the two remaining “members” of the “axis” – Iran and North Korea – tried to buttress their security by other means besides their sovereignty.

In sum, the arguments made by Prime Minister Netanyahu that “The year is 1938 and Iran is Germany” and similar arguments made by other Israeli leaders (for example President Shimon Peres, one of the architects of Israel’s nuclear project, who, in 2009, argued that the world has no choice but to compare the threat posed by Iran to that of Nazi Germany before World War II), were exaggerated.

The existential fearmongering about Iran also had a paralyzing effect on public debate within Israel. The Israeli daily Ha’aretzfound that in all of Prime Minister Netanyahu’s speeches before the UN General Assembly from 2009 to 2014, he mentioned Iran 167 times – but “peace” only 106 times and “Palestinians” a mere 59. While debate raged over the existential threat posed by Iran, other potentially crucial problems for Israeli society were overlooked.

That is why the Iran deal could be so good for Israel. Its success will remove Iran as an existential issue in Israeli politics, opening up room for a more nuanced debate over Israel’s policy concerning the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. That may be bad news for Prime Minister Netanyahu and other proponents of the de facto binational state in Israel-Palestine, but it means hope for all those who wish to see Israel as a nation-state within pre-1967 borders, enjoying international legitimacy and peaceful relations with its neighbors.

Among other things, Israel could even consider adopting a more pragmatic approach towards Iran. Such an approach would acknowledge Iran’s interests in the Middle East while safeguarding Israel’s regional interests. After all, both states have little to gain from the weakening and possible disintegration of Arab states such as Iraq and Syria; from the rise of predatory non-state actors such as the Islamic State; and from full-fledged military intervention by external powers in the region, most recently Russia.

After decades of mutual fear, animosity and harsh rhetoric between Israel and Iran, the time may have come for mutual accommodation.

Translator: Michelle Bubis