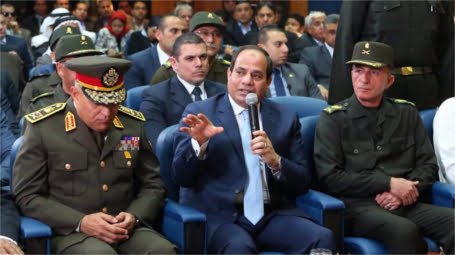

July 23, the anniversary of the Free Officers’ Revolution is a particularly festive day in Egypt. On July 23, 1952, a group of officers headed by Gamal Abdel Nasser topped King Farouq and brought an end to the monarchy in Egypt. This year, the Egyptian President, Abdel Fatah al-Sisi, stood before the young graduates of the military academy and warned them in his speech of “rumors, loss of hope and feelings of frustration,” whose purpose, he claimed, is “one and only one: to mobilize people to destroy the state. ” Sisi claimed that over the past three months, Egyptian authorities identified 21,000 rumors, or “fake news,” which were spread to achieve these goals.

It is unclear how and by what technological means these “rumors” were identified, but several days after the speech, the Egyptian parliament passed three bills that would make it easier for Egyptian authorities to fully censor media publications: the first, the law of regulation of media; the second, a law regulating the National Media Committee; the third – a law regulating the National Broadcasting Authority. According to many in Egypt, the purpose of these three laws is to make it difficult for reporters to operate in the country, and essentially to grant authorities near-total control over the messages transmitted to Egypt’s 90 million citizens.

This latest legislation should be seen in the broader context of a systematic assault on press freedom and independent media in Egypt. Over the past several years, authorities have jailed journalists; blocked access to hundreds of websites, including website of independent journalists and blogs after they were classified as undermining national security; opposition voices have been silenced; and the regime took over independent media outlets.

One case, which is emblematic of other cases, is the arrest of the independent journalist Ahmed Sakhawi. Sakhawi was arrested for the first time with his fiancée in September 2017 and was initially accused of spreading false news and belonging to the Muslim Brotherhood, a movement that the Egyptian regime designated as a terrorist group in 2013. It should be mentioned that Sakhawi did take photos for reports published in newspapers tied to the movement. For many months, his lawyers reported that he is being tortured and that he even tried, twice, to commit suicide while in detention. According to several reports, he is being held in one of the maximum-security military prisons in the country. About a month ago, his detention was extended by additional 45 days.

As one would expect, these steps have generated a great deal of negative publicity. The Egyptian regime, nevertheless, claims that these steps are necessary for preserving the stability of the state. Indeed, since coming to power, Sisi has spared no effort to quash and prevent any popular mobilization, on the ground or online.

Despite this, one of the prominent hashtags in the Egyptian Twittersphere over recent weeks has been #Irhal_Ya_Sisi, meaning “Sisi, get out” – a clear reference to the popular protest movement in Egypt in 2011, in which protesters used the same slogan, but directed it at Egypt’s President at the time, Hosni Mubarak.

One of the significant differences between this online protest campaign and the public anger expressed on Egyptian social media in recent years is anonymity. Tens of thousands of users on social media used this hashtag in their posts, and the overwhelming majority were careful and chose to write anonymously, at times even opening special accounts dedicated to this. This was done to evade the social media monitoring tools deployed by the Egyptian regime.

Another apparent difference in the messaging on Egyptian social media is the lack of political identification of the users. The overthrow of President Mohammed Morsi in 2013 divided Egyptian society into two: supporters of the Muslim Brotherhood on the one hand, and their fervent opponents on the other. Egyptian authorities labeled the Muslim Brotherhood as “enemies from within,” and did everything in their power to exclude them from the public discourse. At the same time, Egyptian authorities labeled any opposition to the regime as indicative of support for the Islamist movement.

The current campaign against Sisi reflects ongoing frustrations of large swaths of the Egyptian public, whether they are Muslim Brotherhood supporters, or opponents of the Islamist values of the movement. The photos shared by Egyptian users on their accounts do not indicate affiliation with any movement, and the narratives of the different parties and factions in the country are absent. Naturally, however, the supporters of the Muslim Brotherhood are trying to exploit this societal displeasure to lambast Sisi.

The poster listing Sisi’s failings shared on social media

For example, one poster that was shared thousands of times carried the headline “Sisi lies and does not respond.” The poster was signed with the hashtag #Sisi_get_out and the authors list the reasons why Sisi should leave his post. Those include: betraying his promise to the people that he will retire if asked; not upholding his promise to establish a committee for national reforms; releasing from prison, due to political motives, people accused of murder (the name being mentioned is that of Hesham Talaat Moustafa , an Egyptian millionaire who murdered the Lebanese singer Suzanne Tamim and was pardoned by Sisi in 2017); and the main cause for public displeasure – pushing Egyptians into an abyss of poverty.

The poster listing Sisi’s failings shared on social media

It seems that one of the main dilemmas Egyptian decision-makers are facing (along with other significant challenges Egypt is dealing with at home and abroad) is determining the extent to which the masses should be allowed to vent their frustrations and express their opposition. At this stage, the regime is adopting a policy of zero tolerance toward any criticism of the president, his performance or that of other power centers in the country. However, employing the most sophisticated technological tools to eradicate any expressions of opposition online may result in having to face a much more significant mobilization, in the form of millions erupting into the streets, as we have seen in Egypt several times over recent years.