In this essay I will argue that the resolution of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict must address the conflict’s prominent colonial characteristics, more so than the failed attempts at resolution by partition. The reconciliation will stem from a joint Palestinian-Jewish struggle with international backing, and will bring about a resolution in the form of a single democratic and bi-national state between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea.

The results of the Knesset elections of November 2022 and the rise of the political right are regarded as a seminal event in the process of diminishing the possibility of resolving the conflict through a territorial partition based on the 67′ borders. But this is a common misunderstanding of the conflict and therefore also of its possible solution. First, the roots of the conflict lie not in the occupation of 1967 but in the results of the 1948 war and the triumph of the enterprise of Zionism as a settling colonialism. This enterprise was born in Europe, and within its framework emerged the consciousness of a modern Jewish nation group. The Zionist movement succeeded in imparting to the world the idea of Jewish self-determination in Palestine, and in convincing the decision-makers in the powerful countries of the day to support its realization. In 1947, the Zionist enterprise received an unprecedented seal of approval in UN Resolution 181 – the partition resolution – which was supported by the two superpowers, the Soviet Union and the United States. This resolution gave de-facto support to ethnic cleansing, and to a driving out of Palestinians from their homeland as a necessary by-product of the establishment of a Jewish state.

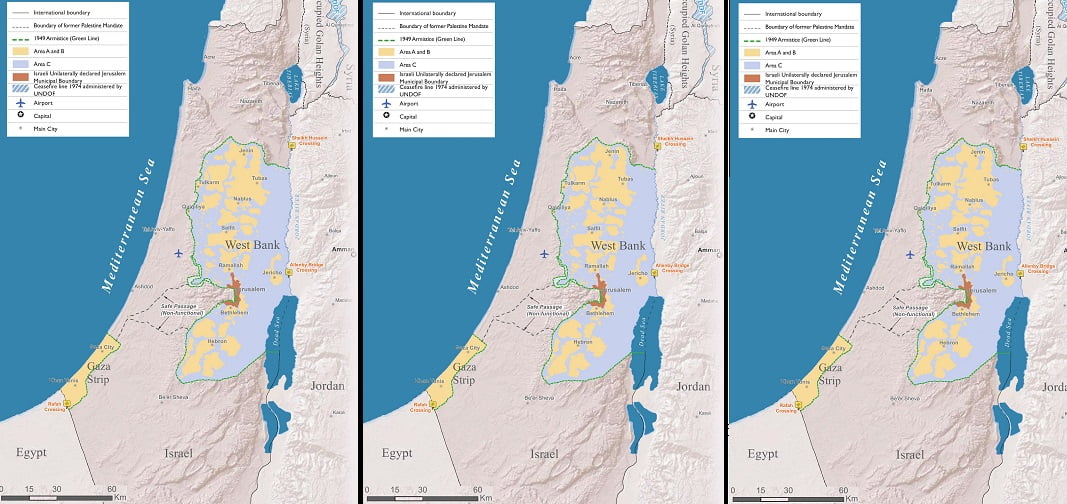

Second, the territorial partition of Palestine, which is a colonial idea, has served Israel, or at least certain sectors within it, to demonstrate that it is interested in resolving the conflict while at the same time proceeding with the task of ethnic cleansing, expulsion, and the expansion of its control. On the opposite side, the idea served part of the Palestinian leadership to cultivate the aspiration for independence and self-determination in a part of the Palestinian homeland; in this way it reinforced its own rule as a leadership that supports resolving the conflict. At the same time, the idea also serves the international community, including most leaders of the Arab world, to avoid confronting the central question that emerges from the reality created in Palestine in light of the conflict that is ongoing for over one hundred years.

Confronting the objective reality is the key to a just solution in Palestine. There is a settler colonialism in this land, within which, over the years, an apartheid regime has taken hold. It is true that Netanyahu’s latest government gives this reality a more explicit and clear-cut expression, but this has been the situation from 1948 to the present day. Anyone who visits the Galilee, the Negev or mixed cities, indeed anyone who turns a critical eye on Israeli public institutions, including universities, the legal institutions, media institutions and other spheres that are supposedly neutral, will easily notice the exclusion, the ethnic dominance, the discrimination based on nationality. The present government in Israel may well make things worse, but it will not create a new reality, as some of the analyses published these days suggest.

By contrast, it is highly possible that steps that the new government has already announced its intention to implement will actually be an important milestone in the process of change that needs to occur in Palestine/Israel. According to this assessment, the present government will contribute to deepening the colonization and thus to exposing the apartheid and finally putting an end to any talk of the relevance of a partition into two states. Moreover, it will sharpen our view of the possible alternatives for the future: apartheid, or reconciliation within the framework of a single state. In doing so, it stands to make a significant contribution, if indirectly, to the struggle to end colonization and Israel’s expanding control and to a shift in the political agenda, from resolution by partition to an eradication of the apartheid situation. This change needs to take place not only the level of the regime, but also in the cities and neighborhoods – by canceling the ethnic separation that exists in them. The practice of preventing Arabs from living in certain towns and rural settlements must end, and indeed a legal change, symbolic and structural, must be enacted.

Redrawing the lines of the battle is a political and moral imperative for everyone involved in this conflict, here and abroad, but it is above all the task of the Palestinians, or more precisely – of the Palestinian elites within the Green Line and beyond it, including in the Palestinian diaspora. While it is true that the Palestinians are the main victims of the reality in their homeland, I reject the argument that it is not the responsibility as victims to propose a way out; indeed, I believe that the opposite is true, if only because it is the basic interest of the Palestinians to change the situation and help bring about the beginning of a process, however long, aimed at reaching a fair resolution in Palestine.

Though the scope of this essay does not allow me to get into details, I would like to offer a preliminary outline for a way out based on several starting points. First, the Palestinians are victims of an evolving settler colonialism and a deepening apartheid, from 1948 to this day. It follows that ending the colonialism and abolishing the apartheid are the paramount task, and this task yields a different meaning to the notion of “national liberation” than the one it has been given thus far. The main goal is not territorial self-determination in part of the homeland, but the establishment of a state and a regime that are based on a substantive democracy and a communal rather than territorial Palestinian self-determination, alongside the Jewish Israelis. On the one hand, this solution entails a negation of Zionism as the state’s official ideology, an ideology that leads to a policy of ethnic supremacy; but on the other hand, it is based on a recognition of the Jewish Israelis as a national group that has an equal right to non-territorial self-determination in the shared homeland. In addition, the proposed solution would bring about a remedy of the consequences of the Nakba and the subsequent deepening of the colonization and apartheid; it will also recognize the Palestinians’ right to the idea of “one homeland, one people and one solution” and will take into consideration the unique characteristics and conditions of each Palestinian group – Israeli citizens, refugees, residents of Gaza, of Jerusalem, and of the West Bank – as well as the right of the Palestinian refugees who so desire to return to the land and partake in the building of a homeland based on equality.

Second, the proposed solution clashes with international resolutions and with a widespread legacy of supporting the two-state solution. The task of affecting a change of consciousness is multi-faceted and complex, and requires great efforts on the part of the Palestinians and their supporters. Part of the infrastructure for the change already exists. Israel, the state that was established on the basis of the partition resolution, implemented a policy that has eliminated any possibility of a territorial partition. It is Israel that has effectively erased the relevance of the partition plan and the possibility of the two-state solution, and in so doing has put the single state solution center stage. In my view, the ideas based on two states, or on two states in a shared homeland, are no longer viable. We are now in a reality of a single state that faces two alternatives: deepening the apartheid, or a solution based on a bi-national egalitarian state.

Third, the process of change – or in the professional parlance, the country’s “democratization” – will be long and convoluted and will take many years, but the infrastructure for it already exists. Two nationalities inhabit this land, and there is no chance of removing either one of them from the homeland; the foundation for a co-existence is already in place. Moreover, there are attempts at collaboration, however modest, in the form of joint actions and organizations in Palestine, which can serve as preliminary models for a resolution. There is also rich international experience with reconciliation processes in areas that suffered from the same elements of settler colonialism and a deep apartheid. From the processes that unfolded in places like Canada, Norther Ireland, South Africa, Iraq or Kosovo we can learn about the possibility of compromise and reconciliation. The international experience suggests that it is especially important to develop a clear vision of a democratic model and at the same time to persist with a popular civilian struggle for decolonization, while also emphasizing the benefit that will come to all citizens of the shared homeland, and not just to the members of one group.

I am aware of the reality in this land and of the dangerous implications of the rise of racist parties to power in Israel. It is only reasonable to assume that colonialism and apartheid will become even more entrenched in the near future, but clarifying the negative circumstances is the key to changing them in the future. Precisely now, Palestinians and Jews who seek peace and equality, as well as their supporters worldwide, from among the people and its leaders alike, may be able to derive usefulness from the racist spirits that now predominate Israel. Now is precisely the time to step up efforts to establish the idea that Palestine is a place for everyone to live in equality and freedom, and that regimes based on ethnic supremacy are doomed to disappear from the world. This was so in Europe in the first half of the twentieth century, it was so in several other cases in the world in the second half of the twentieth century, and it will be so also in Palestine/Israel, perhaps as early as the first part of the twenty-first century.