Searching for the Roots of the Conflict

As the above-quoted decision by the cabinet of Netanyahu’s sixth government attests, the process of “laundering” the illegal colonies in the West Bank is entering a new chapter in 2023. This is a fitting starting point for this brief essay, in which I will argue that adopting a colonial framework of analysis is crucial for attaining an understanding of the Jewish-Palestinian conflict – and by extension, also of its bi-national solution. This is not just an historical or theoretical understanding; it is rather a perception that requires the planning of decolonization actions for the sake of a possible reconciliation and a dismantling of the apartheid regime that is taking shape between the Jordan and the sea.

One of the main issues in conflict resolution involves identifying the roots of the conflicts, that is, the deep causes for their emergence and persistence over time. Attempts to gloss over these reasons are typically doomed to failure, like bandaging a festering wound without first cleaning it. Moreover, ignoring a conflict’s deep causes breeds a culture of denial and deception, which over the years becomes a problem in and of itself.

Until recently, and for over seven decades, the prevalent approach in Israeli, international and even Palestinian circles has been that the core of the conflict in Israel/Palestine is a border dispute between two national movements, in the context of which there is a temporary Israeli occupation of Palestinian territories and the end of which involves creating two states that will exist side by side peacefully. The international community and international law also still support a partition of the land into two ethno-national states. This view distorts the dynamics of the conflict, since based on it, the predominant discourse of the media, academia, politics, and even most peace organizations ignores two deep causes that are no less important: the ongoing process of the colonization of Palestine, and the ethno-class- stratification. In this essay I will touch on the first, and the need to set in motion a process of decolonization as a prerequisite for reconciliation in the shared homeland.

The Colonial Process

There are several types of colonialism, most of them military and economic which are often conflated with imperialism. Here, however, I focus on settler colonialism, which is a distinct type, defined as an organized process in which a group or state seizes control of an area, including its residents and resources, settles it with members of the invading group and administrates it while applying a racial hierarchy. In this process, the indigenous population is usually displaced, expelled and dispossessed of most of its land, resources and political power.

The colonial process can be external – taking place beyond state borders , and defined as a war crime; or internal – applied to disadvantaged regions and indigenous populations, severely harming private and collective rights, often leading to the long-term institutionalization of an apartheid regime, as in the southern United States until the 1960s, Northern Ireland, or South Africa. In the modern era, settler-colonial processes across the world have ignited a long series of murderous conflicts, some of which continue to simmer to this day. Here in Israel/Palestine, an ongoing process of external and internal settler colonialism underlies the Zionist-Palestinian conflict to this day, as suggested by the headline quoted above about the newly legalized settlements.

It is important to note that unlike economic or military colonialism, whose resolution typically comes with the withdrawal of the occupying force – as for example occurred in India, Nigeria, Indonesia or Algeria – in states established through a process of settler colonialism, the settling population remains in place. The settler population is a central factor in the reconciliation process, as has been the case over the past decades in South Africa, Northern Ireland, New Zeeland, Mexico or Bolivia. This realization is important in order to assuage the fears of the Jews of demands that they leave the country. As in the case of other settler states, true reconciliation must include all dimensions of mutual recognition.

Colonialism in Palestine/Israel?

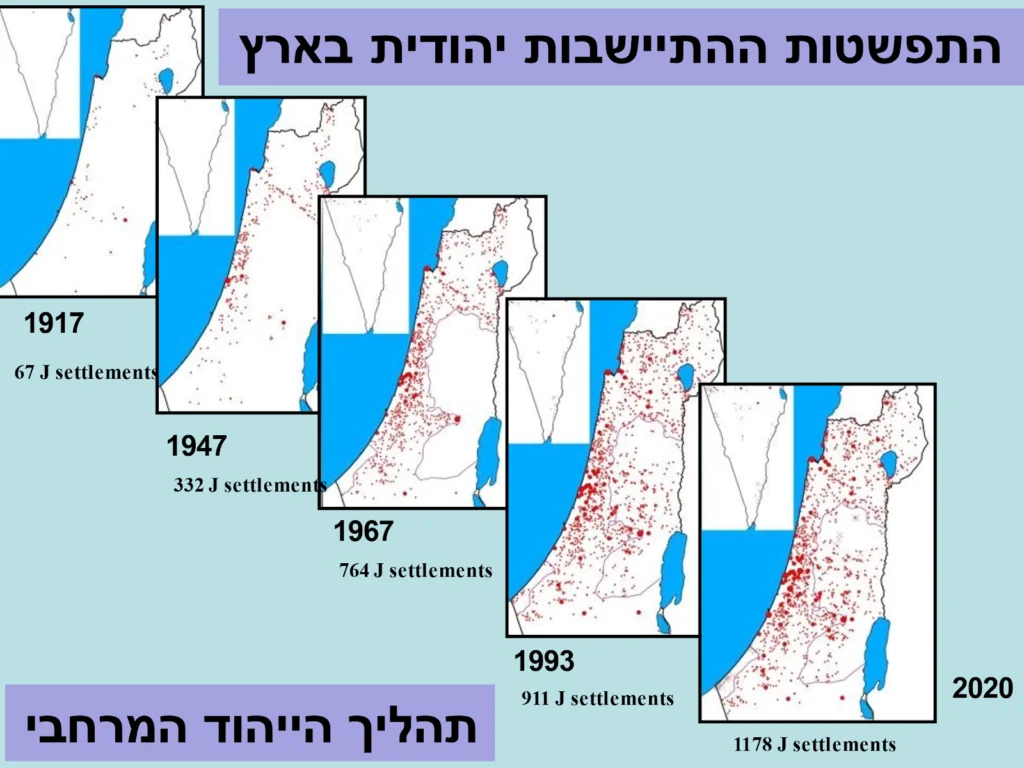

The illustration below presents a consistent and deep process of Jewish colonization of Israel/Palestine, which has included the establishment of nearly 1,200(!) Jewish settlements. At the same time, Israel has destroyed some 450 Palestinian settlements; expelled approximately two-thirds of the Palestinian people, who became refugees in the “Nakba” of 1948 and lost their lands to the settling state; and blocked their return to their land. After 1967, the “Judaization” of the space continued and was based on a military occupation beyond the state’s borders, land expropriation, the establishment of some 250 settlements in the Occupied Territories, and the de-facto annexation of the part of the West Bank known as Area C.

The Process of Spatial “Judaization”

The terminological framing of Zionism as colonialism needs to be qualified in two main ways. First, most of the Jews came to this land in the first half of the twentieth century as refugees, some on the heels of a terrifying genocide. Therefore, the Zionist enterprise in its early stages can be described as a “colonization by refugees.” This state of affairs had a strong impact on Zionism’s sense of its own righteousness, and on the support that it received from Western powers. Second, unlike the political situation in most settler colonial states, the conflict in Palestine/Israel has not been resolved. The indigenous Palestinian people continue to struggle against the process of Judaization and to strive for self-determination.

Theses historical and geographical circumstances, as well as the politics of Jewish supremacy, have created different statuses of Arab Palestinians living under the regime – all of them inferior to the status of the Jews. These include refugees, residents under military occupation or siege, resident subjects in Jerusalem, and second-class citizens within Israel. Jewish-Israeli institutions – nearly totally control the spatial and administrative space between Jordan and Sea, and include the government, the Knesset, the IDF, the Jewish National Fund, the Jewish Agency, the Settlement Division (of the World Zionist Organization), the Israel Land Authority, the various settling movements. These key institutions nearly always exclude Palestinian Arabs, that is – half of the population under the Israeli regime.

These institutions are the deep infrastructure of the conflict’s ongoing colonial character, which gradually disintegrates the legal distinctions between the colonized territories and “Israel proper” and shapes the Israeli regime as that of a state that is not merely Jewish but “Judaizing.” Over the last generation, a de-facto apartheid regime is taking root between the Jordan and the sea, through which the Jewish minority in the land seeks to establish its supremacy on the basis of the so-called Nationality Law, which entrenches this supremacy as a supreme constitutional value. Hence, the attempts of the sixth Netanyahu government to weaken the judiciary during the ‘judicial coup’ of 2023 are intended to pave the way for what should be described as a tyranny of the minority.

Decolonization and Reconciliation

Despite the above, may still rightly ask – why is it important to recognize the colonial aspect for reconciliation? Wouldn’t this cloud our attempts with unnecessary tensions? In short, this step is necessary because the dynamics of colonial control and settlement and their institutionalization form the state’s deep structure and the core of the conflict. Multiple studies point to the link between colonial regimes and waves of resistance, hatred, and terrorism. The definition of colonialism and apartheid as war crimes in international law throws into sharp relief the moral failure inherent in them. Moreover, global experience – for instance, in Northern Ireland, Canada, South Africa, Kosovo, Australia or New Zealand – shows that significant political progress toward reconciliation occurs only when colonial aspects are weakened and ultimately abolished.

A key point for the Van Leer discussion group producing this volume is that effective decolonization must include significant elements of cooperation between all involved groups. This aspect calls for the establishment of bi-national frameworks and alliances within civil society, academia, professional unions, religious institutions, and even in official bodies. At the same time, it is essential to have both a full Jewish recognition of the rights of the Palestinians and a Palestinian recognition of the rights of the Jews and of the deep historical scars both nations bear. In my view, beyond abandoning the violent struggle and consciously accepting the applicability of the international law that recognizes the rights of both nations, the key to mutual reconciliation lies in cultivating a decolonial bi-national historical, emotional, cultural, political and landscape-based connection to the shared homeland.

The vision of decolonization entails comprehensive reforms in almost every area of government and detailing them here is beyond the scope of this essay. For now, let me emphasize the first crucial step, which is changing the discourse so that it focuses on changing the colonial condition and the racist apartheid regime it produces. The new discourse needs to be cultivated in shared frameworks like the Van Leer Institute, social initiatives and organizations, academic campuses or political movements like “A Land for All” binational peace movement calling for decolonization through confederation. The present Van Leer study group is a living example of this kind of discourse. Identifying the roots of the colonial conflict and repairing them is the basis for true reconciliation needed to ensure the future of both Jews and the Palestinians in this shared bi-national homeland. There is no other legitimate future.