My aim in this essay is to think about the ideas of a reconciliation based on a civil partnership “form below,” one that grows out of the actual urban space of East Jerusalem. Observing the current planning processes in the city, which simultaneously describe the existing space and act as imaginings of its possible future/s, allows us to identify moments of change. Based on the planning processes, I will sketch a preliminary outline for actions toward a civil-urban partnership in the Jerusalem sphere, a move that includes a decolonization of the practice of urban planning. This focus shifts the weight of the discussion about Jerusalem from its lofty dimensions to more mundane considerations, in the hope of enabling a proper existence and respectful expression to both national communities that live in the city, and with the aim of acknowledging their already existing interdependence.

My discussion of Jerusalem presupposes that in any political accord that is based on justice and equality between Israelis and Palestinians, the city will remain open and will continue to function as a single urban unit. But unlike the present situation, in which some forty percent of the city’s residents do not have full civil status and suffer systematic discrimination, exclusion, neglect and ongoing displacement, under a just accord the city will have power-sharing arrangements based on an equal distribution of power and on mechanisms of equal representation. Precisely because it is, in my view, impossible, both theoretically and practically, to propose a fair partition of the urban space that would not severely damage the fabric of daily life in the city and the national ethoses of the two communities, Jerusalem should be understood not as exceptional in relation to the possible and desired geopolitical agreement in Israel/Palestine, but as a test or yardstick of a future agreement. In other words, the analysis offered here and the transformative proposal that derives from it are valid and applicable to the entire conflicted space, in which the conflicted geography and the bi-national demography are gradually becoming inseparable.

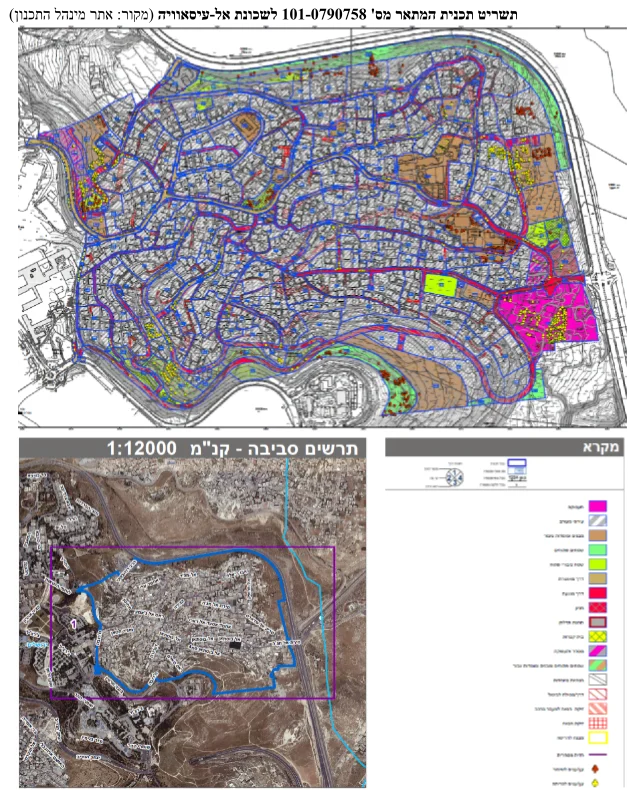

Based on these assumptions, I will present the process of regulating and re-planning the non-formal urban space of the neighborhood of Issawiye. The neighborhood’s new master plan, which is currently undergoing the processes of statutory approval,1Master plan no. 101 0790758 for the neighborhood of Al-Issawiye, chief editor: architect Ari Cohen. See the plan’s blueprint in illustration no. 1. is an example of a change of direction in the Israeli way of thinking about the urban space of East Jerusalem, a change expressed both in the methodology of the plan proposed for the neighborhood and in the possible processes of development that derive from it.2The present planning was preceded by plan no. 11500, which was prepared on the initiative of the residents and with the support of the human rights organization Bimkom – Planners for Planning Rights, and which significantly influenced the present plan. A full discussion of the course of events in this case is beyond the scope of this essay. Four components seem especially relevant to the analysis of the case of Issawiye as laying the foundations for a planning practice based on civil-urban partnership: acknowledging the existing reality on the ground as a normative basis for any future planning; acknowledging the planning as a process of gradual change that is future-oriented; the importance of local relations to the creation of institutional frameworks that promote equity; and the ethical and normative commitment invested in the process.3These categories draw on the idea of “reconciliation as interdependence”: Fanie Du Toit, When Political Transitions Work: Reconciliation as Interdependence (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018).

Unlike other master plans in East Jerusalem, the starting point for the Issawiye plan grounds the acknowledgment of the existing urban space, which is characterized by widespread non-formal development, as a legitimate and sustainable space that force alone cannot undo. This stands in contrast to years of neglect and a longstanding pattern of at best ignoring the non-formal development and at worst actively erasing it by demolishing homes. Even when building plans were approved in East Jerusalem, a rare feat in itself, they were typically aimed at demolishing the existing built landscape and replacing it with a new and more “proper” one. In contrast to these practices, the new master plan reflects an acknowledgment of the existing reality as one of interdependence in which no one side – neither the Palestinian residents nor the Israeli authorities – has exclusive control over creating the space. This recognition is expressed in the development mechanisms proposed in the plan, which enable a regularizing (legalizing) of the existing urban fabric instead of its demolition, and allow for a gradual process of changes and adjustments within this fabric. In addition, recognition of the Palestinian ownership of the land is integrated into the development processes, since the development mechanism proposed in the plan relies on local knowledge and communal agreements about the land ownerships, instead of on Israeli legal criteria. While these differences may seem negligible relative to the magnitude of the problems, they mark a new way of thinking about the East-Jerusalem space. This new perception regards the processes of urbanization that emerge from below as relevant and worthy processes and not as expressions of law-breaking actions that deserve to be erased.4See also Ananya Roy, “Slumdog Cities: Rethinking Subaltern Urbanism,” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 35, 2 (2011): 223-238. It even creates an opening to redefine the conditions for becoming an urban citizen as such that are based on relations of partnership in the urban space and not on a one-sided control.

Yet it is clear that beyond acknowledging the non-formal urban space as an inevitable result of the realities of life in Issawiye (and in East Jerusalem more generally), we must also move toward the understanding that for residents of the neighborhood, the processes by which this urban space was created embody normative values that need to be respected and incorporated into the planning processes. This recognition and this respect are expressed in the innovative mechanisms of development proposed by the new plan, and wherein lies the essence of its originality. These mechanisms establish a collaboration with the residents in the planning processes and a distribution of power between the residents and the urban establishment. They express a replacement of the idea of rigid and predetermined planning with a flexible mechanism, by allowing small groups of land-owners to plan their immediate space together, and as part of that process, to choose between regularizing the existing situation on the ground, expanding it, demolishing or rebuilding, or any combination of these options. This flexibility gives the residents autonomy in designing the space in which they live and posit them as active players in the processes of urban planning. Implementing this flexible mechanism of development will likely require the local organizing of various forms of self-management: both an organizing within the community to reach agreements between the residents; and an organizing designed to mediate between the residents and the local government. Such organizations, if they manage to become established, will afford the valuable chance to experience professional and civil collaboration and to cultivate trust, which in turn can lay some of the foundations for a broad urban partnership as part of future power-sharing arrangements.

Of course, these modest first steps are not enough. Significant resources need to be invested in narrowing the gaps in the level of development and services between East and West Jerusalem, and in correcting past injustices. The element of land has a crucial role in this correction. In the case of Issawiye, there are many lands that lie outside the borders of the development plan and even outside the municipal borders. These lands have been greatly reduced, both to build settlements and develop infrastructure for them, and due to the severe restrictions Israel has imposed on any kind of Palestinian development, restrictions that caused the extensive non-formal construction in the first place. Therefore, expanding the border of Issawiye’s development, fully acknowledging the residents’ ownership of the land, and re-opening the lands that belong to the residents for their own use – all these are complementary and necessary components of any process of a decolonization of the space.

In summary, analyzing the new master plan for Issawiye points to two significant changes in the way of thinking about the urban space of East Jerusalem, which may serve as a first step toward advancing a partnership-based urban planning: a transition from dictating a rigid and final planning objective, based on erasing the current situation on the ground, to imagining a space of possibilities for development and change based on acknowledging the existing reality; and a transition from one-sided decisions imposed from above, to a combination of communal planning processes and collaborations between the community and the municipal government. At the same time, a commitment to normative justice and equity and a constant striving to dismantle the unequal power relations are crucial elements of these processes if they are to lead to true partnership. In this context, the uniqueness of the profession of urban planning lies in its ethical commitment to promote the welfare of the city’s residents whoever and wherever they are. This commitment holds the potential to be a catalyst for deep and expansive processes of building a partnership in other areas as well, based on an acknowledgement of our interdependence as it is reflected in the urban space of Jerusalem.

- 1Master plan no. 101 0790758 for the neighborhood of Al-Issawiye, chief editor: architect Ari Cohen. See the plan’s blueprint in illustration no. 1.

- 2The present planning was preceded by plan no. 11500, which was prepared on the initiative of the residents and with the support of the human rights organization Bimkom – Planners for Planning Rights, and which significantly influenced the present plan. A full discussion of the course of events in this case is beyond the scope of this essay.

- 3These categories draw on the idea of “reconciliation as interdependence”: Fanie Du Toit, When Political Transitions Work: Reconciliation as Interdependence (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018).

- 4See also Ananya Roy, “Slumdog Cities: Rethinking Subaltern Urbanism,” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 35, 2 (2011): 223-238.