At the beginning of 2016, a young Arab citizen of Israel named Nashat Melhem went on a shooting spree in central Tel Aviv, killing two people and injuring others. His act drew public attention to two pressing issues: the intergenerational struggle taking place within Arab society in Israel, and the loyalty of the Arab minority to the nation-state of the Jewish hegemony.

The “Worn-Out Generation” – Arab citizens of Israel born between the 1950s and 1970s – failed to revolutionize the national and civic status of their minority group and grew irrelevant. Their children, known as the “Stand-Tall Generation” – born in the 1980s and 1990s – now recognize the importance of their population size compared to that of the Jewish population, criticize their parents’ timidity, and are waging a determined battle for their rights.

Many nation-states struggle with the dilemma of minorities’ “double loyalty” – to their nation and to their state. Members of minority groups can respond to this dilemma in one of three ways. They can try to assimilate into hegemonic majority society and condemn any form of violence that may threaten them to the point of exclusion, on both governmental and daily levels. They can adopt a separatist position, operating independently of the majority group through civil society organizations and non-parliamentary movements that provide a moral, political and financial basis for their civil struggle. Or, should the exclusion and its consequences increase, they can choose the path of a violent struggle.

The choice of the Arab population in‘Arara not to turn Melhem over to the Israeli authorities, and the choice of Arab teens not to take part in civil service initiatives, are two sides of the separatist coin. As long as Israeli law enforcement is not applied in Arab villages and the authorities do not offer these citizens protection from a weapon-rich and violent environment, community members cannot afford to turn in one of their own and risk excommunication or even mortal danger. The teens’ aversion from civil service has similar roots: they refuse to be servants, both in the civic sense of occupying menial, low-paid positions, and in the security sense of collaborating with Israel’s security forces against their Palestinian brothers. “Upright I walk, an olive branch in my hand, a coffin on my shoulder”, wrote Samih al-Qasim in his poem “Muntasib al-qamati, amshi” (“Upright I walk”). Frustrated, alienated and disappointed, the young adults of the Stand-Tall Generation are challenging the systems that try to erase them: the Jewish nation-state that erases them as a group, and the patriarchal system through which their fathers, older brothers and sheikhs erase them as individuals. The slim chances of finding adequate employment and achieving financial stability, compounded with the high dropout rate and the large numbers of juvenile delinquents (more than in the Jewish population), alongside disappointment over the modus operandi of the traditional Arab leadership and dwindling trust in state institutions – all these work together to drive Arab teens in Israel seek avenues for expressing their growing rage.

Some chose to boycott the 2001 general elections in response to the events of October 2000, in which police killed 13 Arab demonstrators. Others turned to a symbolic artistic discourse to convey their sense of a liminal and temporary existence, using techniques ranging from silence, hesitant speech and floating to tattooing themselves in Arabic, urinating and sticking pins in their clothes or bodies.

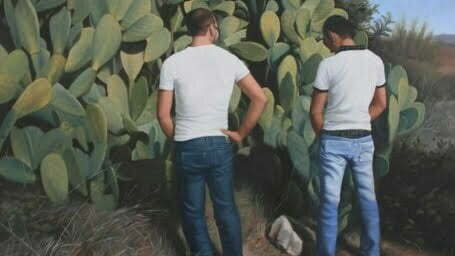

For example, Arab-Israeli artist Michael Halak painted two young Arab men urinating on a sabres plant, challenging the attempt of the “Israeli sabra” to mark out a new territory instead of the borders previously marked the “Arab sabra”. Artist Raafat Hattab tattooed his national identity (“Jaffa, Bride of Palestine”) on the hybrid body of a mermaid in his video “Huria” (“Freedom”), documenting a deep connection to the homeland and the sense of gender liminality (homosexual) and national liminality (Palestinian) of those excluded from the social and national collective. The needles stuck in clothes created by Buthaina Abu Melhem or the pins sticking into the body of artist Samah Shehadeh symbolize a conflicted, tormented, fragmented identity and a sense of relentless personal and universal pain.

Others chose the path of violent struggle. In the 00’s, a terror group affiliated with a global Jihad organization known as “Ansar Allah” was responsible for murdering taxi driver Yafim Weinstein, stabbing a pizza deliverer, torching a tourist bus, and throwing stun grenades and Molotov cocktails at homes and businesses of Christians and Jews in Nazareth Illit. Others planned to grab the weapon of a Border Police officer and attack him at the police station in Daburiyah in 2011. There were also violent riots in Kfar Kana and in other Arab communities in Israel after a youth from the village was killed by the Israel Police in 2014. In recent years, young Arab citizens of Israel have joined Hizballah and ISIS.

Nashat Melhem may turn into a role model for excluded and marginalized Arab teens in Israel. Facebook and Twitter accounts opened in his memory present him as a hero who sowed fear in the heart of the Tel Aviv metropolis, the symbol of the Jewish-Israeli middle and upper classes. He is lauded as the young man who shattered the myth of tight Zionist security control, kept the entire defense establishment and political system on their toes for days, and a resident of the “Triangle” area in Israel who challenged Lieberman’s plans to transfer the population there. At the same time, he is also extolled for revealing the true face of the Palestinian Authority, which refused to add him to its list of martyrs. Nashat Melhem broke out of his dismal life and has become a “martyr” and a “national hero”, both within Israel and beyond.

Translator: Michelle Bubis