On July 14, The Democratic Society Congress in Turkey (DTK) a Kurdish-led umbrella group composed of 850 members from all over Turkey, boldly and unilaterally declared Kurdistan’s democratic autonomy, and called for international recognition. Although the DTK includes Turkish members, the congress’s political agenda is predominantly pro-Kurdish nationalist. The best known Kurdish political party in Turkey, the BDP (Peace and Democracy Party), is represented by five members in the congress, along with two co-chairmen of the banned Kurdish party DTP (Democratic Society Party) which was closed down by decision of the supreme court in 2009.

As Jerusalem Post reported on July 23, this Kurdish declaration of autonomy received almost no response from the international community. At the same time the death of 13 Turkish soldiers on the same day, in a shoot out with PKK guerillas in the province of Diyarbakir (which the DTK declared autonomous and referred to as the capital of Kurdistan), escalated tension between Kurds and Turks resulting in clashes in major Turkish cities. Many Kurds were disappointed that the AKP managed to divert attention from the declaration of autonomy to the death of the soldiers. In response the Kurdish BDP party leaders claimed that the Turkish soldiers were killed by the Turkish Air Force in order to cast a shadow on Kurdish democratic demands. Surprisingly, the PKK and eyewitnesses, most of whom are members of the state-organized armed Kurdish villagers against the PKK, confirmed the BDP’s claim.

Resurrected in the aftermath of the AKP’s ‘democratic opening’ towards the Kurds in 2009, the Kurdish political movement claims it has no secessionist goals. Under pressure that time is running short in face of increasing governmental pressure on Kurdistan’s autonomy, the pro-Kurdish DTK unilaterally undertook its own elections on July 24, in 43 provinces. Although formally the Kurdish movement remained faithful to its claim of “no space for secessionism”, statements by DTK officials contradicted such a claim. On the day of these Kurdish ‘illegal’ elections, the head of the city council in dominantly Kurdish Diyarbakir, regarded the elections as the Kurdish move towards self-determination.

DTK’s latest meeting on July 29 ended up deciding that the Kurds are ready to pay the price for their autonomy. Hence, Kurdish nationalism, in a blurred secessionist form, seems to have won over the moderate Kurdish intellectuals’ earlier calls for a democratic Turkish republic, where cultural rights of the Kurds should be secured by a new constitution. On the other hand, the AKP recently announced that the project to resolve the Kurdish question through promotion of democratic rights will continue. The main principle of the government’s action is to isolate the Kurdish question from the influence of PKK and other pro-Kurdish nationalist organizations, and to ensure the Kurds that they will enjoy democratic rights on an individual level. Yet, the project seems to have no Kurdish support anymore. In an interview to the Turkish left-wing newspaper Radikal on July 25, Bengi Yildiz, a Kurdish member of parliament and the Kurdish Peace and Democracy party (BDP) representative in the DTK, defined Kurdistan’s borders as including almost all Kurdish inhabited provinces in the country. Bengi also asserted that the upcoming autonomous Kurdistan should not pay taxes to Ankara.

One could argue that it was not the DTK itself but the AKP’s democratic opening that dragged the Kurds into a more nationalist discourse. After the Underground leader, Öcalan, was captured and jailed, Kurdish parties had abandoned independence claims . However, this did not mean that the PKK declined the national aspirations of the Kurdish masses. With the AKP’s ‘democratic opening’ towards the Kurds, it can be argued that the PKK found itself under threat of losing its raison d’être. Return to the original cause, namely Kurdish secessionism, was suddenly declared exactly when most Kurdish intellectuals declared their support for the government’s democratic project.

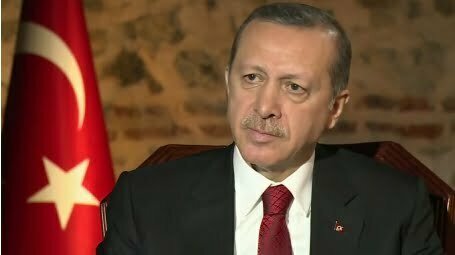

Erdogan’s AKP has so far proved that its triumph against the former elites of Turkey, including the military, was based on meticulous political calculation. The question that rises at this point is whether the AKP failed in calculating the results of its ‘democratic opening’ initiative, which apparently resulted in an resurrection of Kurdish nationalism, or whether the AKP’s failure was a carefully planned move intended to give rise to Kurdish political rights.

The latter option sounds more logical to me. An indirect effect on the Kurdish political movement by the AKP in terms of pushing it again into a nationalist stance would eventually result in Kurdish autonomy in Turkey, and this type of indirect plan is not beyond the AKP grasp. In other words, the AKP must have calculated that once it attempts to replace Kurdish political bodies with selected other Kurds – as has already happened during the short-lived democratic opening – the PKK and its legal extensions would return to their original cause: Kurdistan’s historical right of self-determination.

From my perspective, we might be witnessing a controlled transfer of power to the PKK. This project might have been designed to counter the domino effect emanating from Kurdish Federal Region in Iraq that could have taken the PKK and its goals towards an end that is no more controllable by Turkey. Erdogan and the AKP knew that any political party that initiates such a project is in danger of being eliminated by the Turkish nationalist opposition. Therefore, an indirect effect on Kurdish nationalism, while keeping the Turkish-nationalist elements in its political discourse sounds as the most secure way for the AKP to resolve the Kurdish issue.

Ceng Sagnic is a freelance correspondent for Kurdish language newspapers and is writing an MA thesis at Ben Gurion University