In this article I argue that the State of Israel, in its current legal structure and the political discourse it promotes, is reshaping Jewish identity in a way that devoids it of components that were essential to it for generations. I will also argue that the present use of the term “Jewish” in Israel, along with the legislation of the Nation Law, pose a threat not only to Israel’s non-Jewish citizens but also, and possibly primarily, to Jews who are interested in the continued existence of traditional Jewish identity. At the end of the article I will pose a different structure of Arab-Jewish partnership, based on neutralizing the power structure created under the auspices of Judaism and at its expense.

The political secularization of Judaism

Philosopher Giorgio Agamben proposed that secularization is a political act that replaces a power structure that is fundamentally religious and based on the separation of the sacred and the profane, with a new power structure based on the same separation but on the terrestrial level. In that sense, the replacement of the religious power structure with a secular power structure can certainly be performed by religious people, who are sometimes even more successful at transferring the religious language and culture from a spiritual focus to a political and terrestrial focus. Secularizing revolutions replace God with a supreme leader, country, or nation. Secular nationalism demands devotion from its believers; it has its own sacred institutions: in Israel they were even given the names of the ancient religious institutions, such as the Knesset “sanctuary,” or the “temple of law,” so that language constitutes a direct association between the religious sacred and the secular profane.

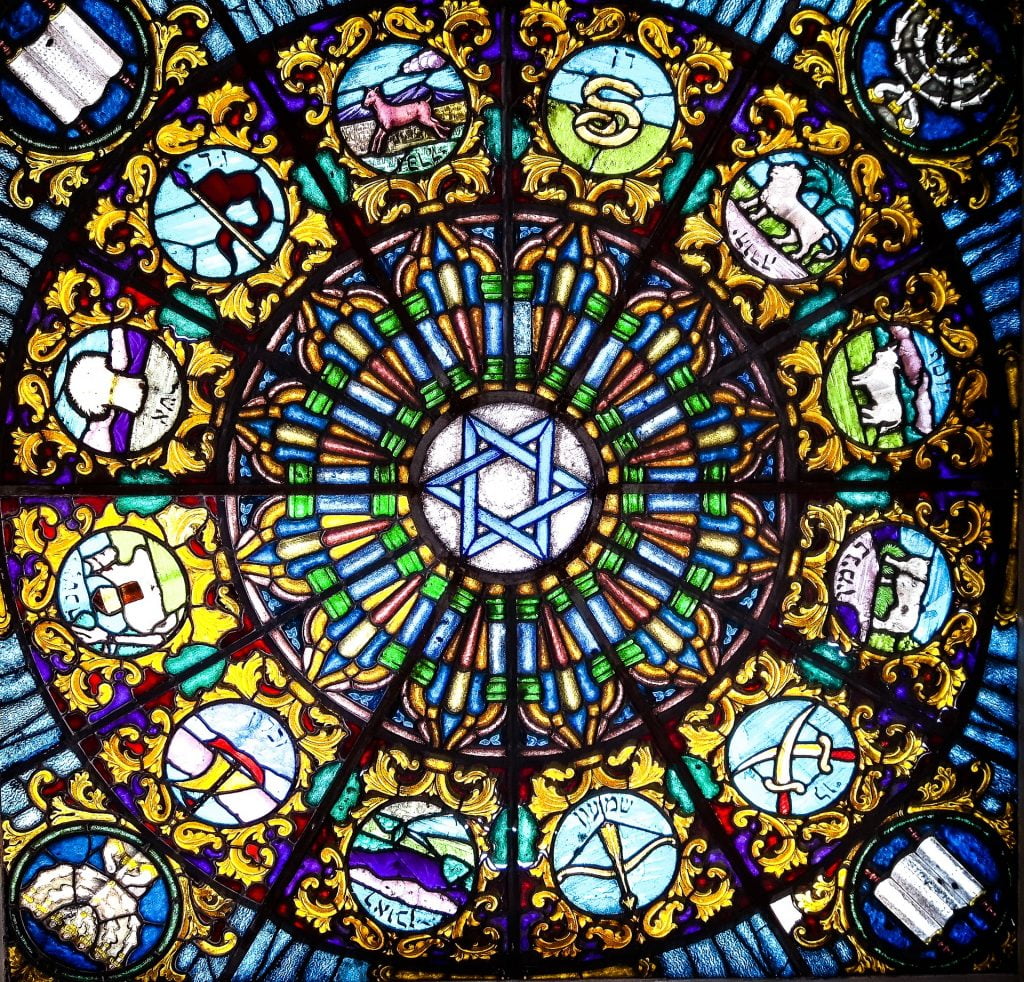

Of all modern Jewish responses, examination of political Zionism against these definitions shows that it sought to substitute divine redemption at the center of traditional Judaism with a realization of concrete political autonomy, while maintaining the traditional separations and secularizing them. I propose that contemporary Zionism including religious Zionism cannot be understood without paying attention to the fact that it is based on the secularization of Judaism. The traditional categories, language and symbols are maintained but receive new meanings. The blurring between Jewish religious language and Israeli secular language always happens in one direction: in order to reinforce the legitimacy of the secular-political power structure, by reinforcing the association between it and sacred concepts in collective Jewish memory. In that sense, “secularization is a kind of repression” – it leaves intact the forces with which it contends, but moves them from one location to another.

Traditional and pre-political Judaism was primarily a way of life that included performing commandments and anticipating redemption, which is to say, a constant engagement with categories of sanctity and profanity, and the belief that there is a transcendental commander, and a desire by the commanded to touch something beyond, to march towards a future that is going to be redeemed. With the establishment of Israel, a new Jewish power structure was established, where Judaism in its secularized version still plays a central role in creating separations and categories. It is at the center of the Israeli power structure, sharpens categories, draws the circle of affiliation, validates the ownership of one group and dispossesses the other. It is a world in which Judaism is still at the center, but its function has completely changed, and instead of a system of divine laws that posed an alternative to the existing political order, it became a narrow nationalism that strengthens the legal structure of the state.

In the absence of a redemptive-miraculous dimension, Judaism is the justification of the power structure, and its maintenance is the telos of Israeliness. If the state uses force, it is because it is the faithful representative of the Jewish people, it is in charge of the continued existence of Judaism, and therefore its strengthening is the strengthening of Judaism. It is a Judaism without content, a Judaism which is its own reason, means and goal. Thus, the political use of the concept of “Jewish” in Israel is always circular: the country is Jewish, therefore it must strengthen its Jewish identity, so that that identity strengthen its definition as Jewish. The definition of the country as “Jewish and democratic” and the passing of the Nation Law are among the starkest examples of that trend. If the legal definition of the word “Jewish” is extremely elusive in Israeli law, the reason is that political-Israeli “Jewishness” has no essential content. In the existing Israeli law, “Judaism” is not a justification for the legitimate use of force by the state, but is the force itself.

Another aspect that illustrates the revolution Judaism has undergone within the Israeli framework is the use of the term “messianic.” Traditional messianism sought to neutralize the human power structure and pose a utopian alternative that disrupts the historic continuum; messianism in the Israeli discourse, on the other hand, is actually the radicalization of the political power structure. The leaders of Zionist messianism are precisely religious Zionism, which radicalizes the political secularization of Judaism, usually as a golem turning on its liberal Zionist creator. It is an anti-traditional Judaism, which views full redemption not as the disruption of national time but as another step that radicalizes the current trend. It seeks to strengthen the political power structure by absolute control of a larger territory, sharp separations between Jews and non-Jews, building a temple without Divine Presence, theocracy without prophecy. Namely, a radically secularized religious power structure.

The question of Arab-Jewish partnership in Israel

Heretofore I tried to show that Israel is leading a years-long struggle to control the shaping of Judaism, expressed in two ways: first, by suppressing traditional Jewish identity and subjugating it to a narrow national identity that serves its political interest; and second, by an instrumental use of the term “Jewish” to create categories and separations between Jews and Arabs. In the next section I will argue that promoting Jewish-Arab partnership can play an important role in neutralizing the Israeli power structure, for the benefit of both groups.

Today, the Arab-Jewish partnership discourse is usually led by people with a weak particular identity – Jews and Arabs whose Jewishness or Arabness are perceived as incidental and which does not carry extreme significance for its owners. At the basis of this partnership is a liberal vision that seeks to create a joint civil identity at the expense of weakening the particular identities. This new citizenship will ultimately allow the integration of the minority group into the majority group, or in the best case the creation of a new group that will be formed on the ruins of the existing groups. I think this liberal partnership vision is doomed to failure, because it is based on an idea of progress and forgetfulness, so that it cannot supply any justice towards past generations. At its basis, it accepts the existing power structure and perceives the Israeli-Palestinian conflict on a chronological timeline, extending from groups fighting for their ethnic autonomies to groups that “grew up” and are now ripe to merge with each other.

I argue that Arab-Jewish partnership to generate change and allow the disruption of the chronological history of the conflict must be built on a completely different foundation. Not out of the desire to cultivate a new civic identity, but out of the desire to liberate both groups from the categorization and identity reduction that was imposed on them. It is not necessarily a “religious partnership,” just like it is not an anti-liberal partnership. It is a partnership based on a different treatment of the past, recognition of the existence of a Jewish identity and a Palestinian identity that exist beyond the narrow borders of Israel/Palestine. Likewise, it is a partnership that seeks to neutralize the power structure that was built here, out of the understanding that such neutralization will go through disrupting Israeli time and exposing the repressed voices of the past within the present. The clear signal of that disruption is that justice towards past generations is intertwined with the restitution occurring in the present. When the power structure is neutralized, when the historic continuity is disrupted, the moment of rupture allows the reshaping of the past and redrawing of the future. Such partnership, if it arises, might succeed precisely because it allows a fertile dialectic between past, present and future and focuses them in the here and now.

Walter Benjamin, in his theses on the concept of history, invites the reader to renounce the “homogenous and empty” time of progress, which turns the present into a transition point between the past and the future. When the present is not a silent point between two time points on the same line, it allows historic events to be reshaped. The past is met within the present, infuses it with new meaning, and thus is written “a secret platform between past generations and our generation.” In many senses, this brief essay is written out of the feeling that such a disruption is needed in the continuity of Israeli-Palestinian history, which does not lead to any foreseeable solution. Such a disruption can draw its power from the past heritage of both groups, demand suspension and ask what the essence of the Zionist project is in relation to Jewish identity and whether that essence is desirable to most of the residents of the land, both Jews and Arabs. The answer of this question should enable a reshaping of Israeli time, to do justice with past generations and offer a correction for this generation.