In recent months, dramatic changes took place in the Maghreb: The Tunisian President, Essebsi, passed away, forcing a new election that is preoccupying the active and turbulent political scene in the country. In Algeria, mass demonstrations continue even after the removal from power of President Bouteflika, while the civil war in Libya is escalating further. In light of these developments, Morocco appears to be far removed from this turbulent region, since the main events taking place across the Kingdom are multitudes of cultural festivals in a variety genres of entertainment, music, folklore and cinema.

Dozens of festivals are held in Morocco throughout the year, most of them enjoying governmental support, and even under the personal patronage of King Muhammad VI. Since coming to power twenty years ago, he has turned cultural festivals into a thriving industry. At summertime, several international festivals take place in Morocco, attracting large crowds of locals as well as foreigners, which are seen as part of the kingdom’s touristic attractions. The main festival is ‘Mawazine – the Rhythms of the World’ in Rabat, which features well-known pop stars from the United States and Europe, alongside major singers from the Arab world, Africa and Morocco itself.

Another music festival was held at the same time in several coastal cities, sponsored by Maroc Telecom. For the ninth year in a row, Marrakesh hosted the ‘Laugh Festival‘ featuring stand-up comedy performances. In Meknes, the ‘International Festival of the Arab film’ was organized this year for the first time, joining multiple other film festivals hosted across Morocco in recent years.

At first glance, it seems that the sole purpose of these festivities is to entertain the masses at home and create a positive brand for the kingdom abroad. A deeper examination, however, shows that their execution and the themes reinforced through them reflect the multicultural national identity that the Moroccan monarchy wishes to foster, as well as its political and social agenda.

Morocco did not undergo a revolution during the “Arab Spring,” and the king continues to hold a supreme position in the political system. At the same time, the regional turmoil and protests inside Morocco led to changes in the Moroccan constitution, which in its current iteration highlights the ethnic, linguistic and cultural diversity of the kingdom – which is now seen as a source of strength, and not a phenomenon that needs to be combatted or erased, as it is seen by other regimes in the region.

According to the amended Constitution, Morocco is a state that preserves its national identity by “the convergence of its Arab-Islamist, Berber [amazighe] and Saharan-Hassanic components, nourished and enriched by its African, Andalusian, Hebraic and Mediterranean influences…”

The Constitution also emphasizes the values of “openness and [religious] moderation” of the Moroccan people, in addition to Morocco’s affinity to the Maghreb and the Arab and Muslim worlds. It also calls to strengthen Morocco’s relations with countries in Africa and in the Mediterranean. The festivals, so it seems, seek to bolster these elements of the complex and multi-varied Moroccan identity.

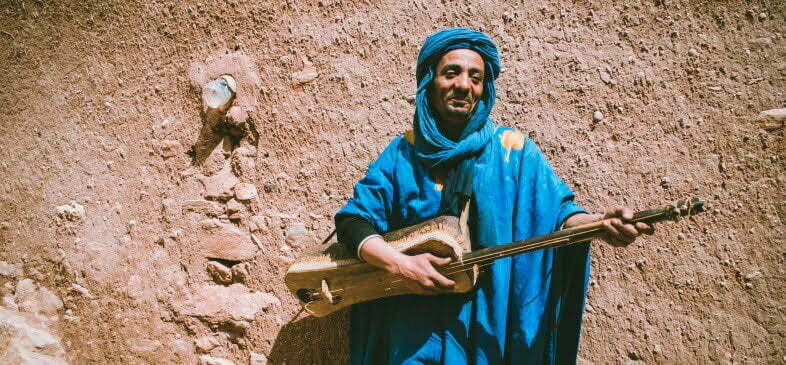

The ‘Fes Festival of World Sacred Music‘, for example, highlights the moderate character of Moroccan Sufi Islam and promotes dialogue between religions and cultures. Many festivals promote Amazigh culture, after Tamazight became an official language in Morocco in the amended constitution in 2011. These festivals also feature discussions and workshops regarding Amazigh identity, alongside musical performances and other types of entertainment.

The Raï Festival, a musical genre originating in Algeria that has become popular internationally due to the North African diaspora in Europe, has been held for over a decade in the city of Oujda, near the Moroccan-Algerian border. Interestingly, despite the tense political relations between these neighboring countries, Algerian artists often preform in Morocco, showing that culture is able to bridge between peoples of the region whereas politics usually fails.

The seasonal festival (‘Moussem’ in Arabic), which takes place in the desert town of Tan-Tan in southern Morocco, seeks to preserve the customs and traditions of tribes of this region. During the festival, members of these tribes gather in hundreds of tents and hold singing and dancing performances, as well as camel and horse races. The festival was recognized by UNESCO as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity worth preserving. It also hosts guests from other countries from Africa and the Arab world, most notably the United Arab Emirates, which also strives to preserve tribal nomadic folklore.

The Gnawa and World Music Festival, which takes place in the city of Essaouira, on the Atlantic Ocean shores, seeks to preserve the music, dance and Sufi rituals developed by African slaves brought to the area in the 16th century. The existence of the Gnawa people and culture in Morocco, which are also present in neighboring west African countries, point to the kingdom’s deep ties to the Black Continent. In recent years, as Morocco positioned itself away from the Arab world and resumed its membership in the African union, this affinity has become particularly evident.

In 2018, for example, ‘The Museum of African Contemporary Art Al Maaden’, was established in Marrakech. Artists from across the continent regularly attend the various festivals taking place in Morocco, which often feature discussions and lectures on issues high on the continent’s agenda, such as the migration from Africa to the Maghreb and Europe, or the state of African art in the diaspora.

There are two other important festivals in Essaouira: ‘The Spring Classic Music Festival’ and ‘The Atlantic Andalusian Music Festival‘, which also reflect the geographical and cultural intersection of the kingdom. Its close connection to Spain and France, the colonial countries that ruled it in the past, is reflected, among other things, in the dominance of the French language in Morocco. In addition, within the intercultural dialogue that takes place at the festivals, Jewish culture is also highlighted, and even the Hebrew language. Jewish and Israeli artists, such as the Andalusian Orchestra of Ashdod and singer Neta Elkayam, performed at these festivals.

Beyond multiculturalism, the festivals in Morocco appeal to various sectors of the population that the kingdom wants to influence, and particularly the youth. The festivals are one of many tools of combating radicalization among them. The festivals also foster the involvement and public engagement of women, whose status in Morocco has experienced a significant improvement, with the encouragement of the palace.

It is worth mentioning that the multitude of festivals in the kingdom often face domestic criticism, especially due to their high cost, given the financial hardship of many Moroccans. Islamists criticize the permissive and Western culture that they believe is being promoted by some of the festivals. Questions of commercialization and restrictions on freedom of expression are also raised.

Despite this, the festivals in Morocco reflect the success story of the multicultural and inclusive model fostered by the kingdom, and it is evident that the regime’s significant investment in this sphere leads to greater openness among Morocco’s diverse communities and sectors. This discourse contributes to the democratization and liberalization in the kingdom, which at the same time manages to maintain stability, as opposed to its neighbors.