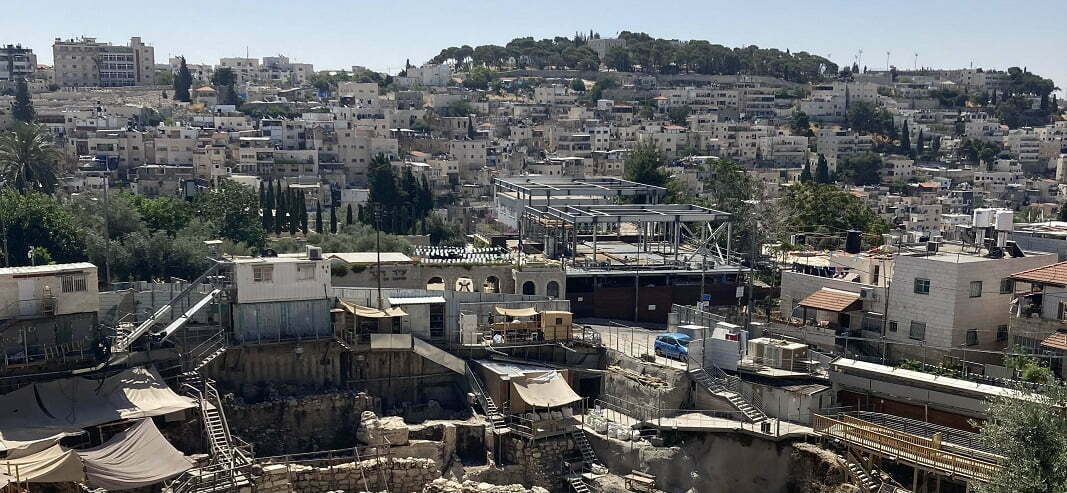

The underground tunnels that are part of the archeological site of City of David in Jerusalem are narrow, humid, and dark. Visitors walk there on stones that about three thousand years ago formed streets in a small ancient city where the Judean people had lived, on a hill just south of the Haram al-Sharif today. They may have had a king by the name of David, though the evidence for that is scant: only one inscription from the ninth century B.C.—in Tel Dan, not Jerusalem—tells us about the victory of the king of Aram on the kings of Judah and Israel, mentioning the House of David. Still, many people believe that Biblical King David existed. Many people also believe that Jews today are linked to the ancient Judeans, even though no evidence supports this assertion. It is the kind of arguments that connect people in Athens today to the ancient Greeks and people in Rome to the ancient Romans—again, with no evidence whatsoever. The City of David is an organization that was founded to act on that belief. This is an organization of Jewish settlers who seek not only to create a narrative about continued Jewish presence in Jerusalem’s ancient past and today, but also to reclaim the area from the people who have lived there for generations: Palestinians in the neighborhood of Silwan. The archeological site is one key tool in their project of violent displacement in the service of an imagined Jewish supremacy.

On Wednesday, 15 June, a group of students from the US, Cyprus, and Israel/Palestine walked in one of those tunnels. They were there in the frame of a study tour on divided cities that I planned and led together with partners from the Hellenic Studies program at Stockton University in New Jersey, where I teach Holocaust and Genocide Studies, and from the Cyprus University of Technology. The group had been to Nicosia in Cyprus the previous week. Students from Stockton University joined Greek Cypriots, Turkish Cypriots, Israeli Jews, and Palestinian Arabs to try to identify in this comparative framework contemporary and historical factors that raise new questions and suggest new possibilities to think, see, imagine, live, and act beyond the walls of segregation and state violence in both cities. What happened next, however, offers very little in way of hope.

As the group was entering the tunnel, eighth-grade students in a group just behind us noticed a Black student in our group, the last to enter the tunnel. They immediately started to laugh at him, making strange sounds, calling him “sexy,” and shouting names of countries in Africa. As we entered the tunnel, this racist spectacle quickly expanded and escalated. As if in one voice, the class started shouting “war, war, war, war,” followed by singing of an Israeli fascist song that wishes Palestinians, “may your village burn down.” The eighth graders did not know that there were two Palestinians in our group; rather, it seems that their anti-Black racism triggered their anti-Palestinian racism. It was, however, no coincidence that this happened in a tunnel that functions, as mentioned, within an archaeological site that aims to bring about Palestinian destruction. The eighth-grade students, in other words, were learning exactly what the City of David was aiming to teach them.

Finally, our group exited the tunnel. I waited to talk with the teacher of the eighth graders, who walked behind her class. I imagined that she would apologize, acknowledge the severity of the situation, and promise to discuss this with the students. Instead, she brushed it aside: she claimed not to have heard the racist calls against the Black student in our group, she argued that “may your village burn down” is nothing more than a soccer song, and she suggested that her students acted the way they did because they were tired. Not a word of apology, no acknowledgment. I then noticed that her class also included a Black student. It seemed that his presence in that class did not teach the other students much—nor did it seem to trouble their teacher that he had just seen and heard the violent anti-Black racism of his classmates.

Our students therefore witnessed how racism, division, and violence are taught, encouraged, performed, and legitimized in Israeli society—how the settler ideology of the City of David figures as part of the educational agenda in Israeli schools.

This requires some response, I thought, and so I wanted to know the name of the school: she told me that they are an eighth-grade class in Bereshit school in Rosh HaAyin, a city east of Tel Aviv. Bereshit, “at the beginning” in Hebrew, is the name of the first book in the Bible. It tells a story of creation, but it also includes tales warning us about the destructions that befall societies that lose all moral sense. The destruction of the sinful city of Sodom by God is one such story (Genesis, 19). The Hebrew patriarch Abraham begs God to save the city should he find there fifty righteous people, later managing to reduce the number to ten. Yet Abraham could not find enough righteous people.

Among the eighth graders, however, there was at least one, a student who apologized to the Black student in our group already in the tunnel—he tried to shout his apology into the air a couple times, but it drowned in the militaristic chants of his group. Outside the tunnel, he apologized again: he felt ashamed of the students in his class. It was a brave act for an eighth grader in this situation, and it highlighted even more the educational failure of his teacher. But it will take much more than one student in an Israeli class for a future in Israel/Palestine beyond the tunnel of racism, division, and state violence.

Raz Segal, Associate Professor of Holocaust and Genocide Studies and Endowed Professor in the Study of Modern Genocide, Stockton University