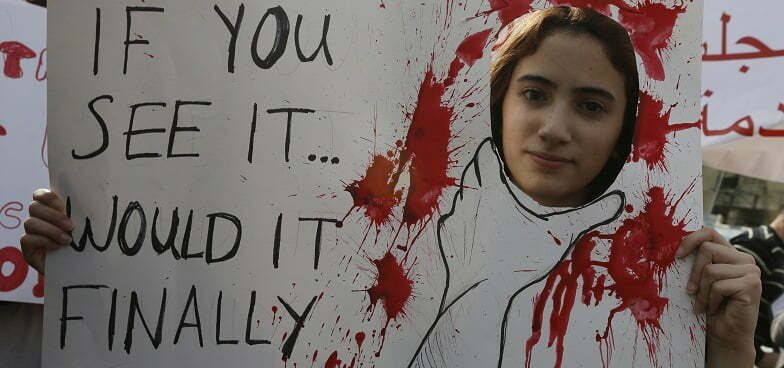

Recently the headlines have been inundated with tragic incidents of domestic violence and the murder of women by their partners, many of them from the Arab sector. Together with the reports from the media, and the criticism that the authorities have been impotent there has been discourse among the Arab public on the subject, as well as a bevy of references to a Muslim man’s responsibilities towards his wife, as is evident from the Quran, the Hadith and early Muslim history.

Early Islamic sources tell of “Ṣaʿṣaʿa Mūḥī l-Mawludāt” (Sasaʿa The Reviver of Baby Girls) – a man who would walk along and save baby girls from the cruel fate of a girls’ grave during the Jahiliyya period, the period preceding the rise of Islam. The story of Sasaʿa is an example of the accepted narrative that emphasizes the gap between Islam and the Jahiliyya: the people of the Jahiliyya worshipped idols, while the Muslim believers served the only one true God; the people of the Jahiliyya buried baby girls in order to prevent the embarrassment they could bring upon the family, and so as to not to waste precious resources on girls who could not contribute to the tribe, while the Muslim believers honored women and gave them a part in their inheritance.

According to the Muslim narrative the Jahiliyya was a period of ignorance, during which they did not believe in the one God, Creator of the World and did not recognize basic morality. One of the characteristics of the period was the humiliating mistreatment of women, and like many other characteristics, the Muslim community and its principles of faith rejected it.

Modern research has doubts regarding the framing of these issues in this way, and exposes the contradictions and the many problems with the description of a sharp turn, so to speak, from the Jahiliyya to Islam. Even more so, according to modern scholarship, the status of women in Islam was not unaffected by the historical transition from idolatry to the faith in one God, but rather is also related to issues of gender, the division of roles, and the rights of women to a place in the public sphere today.

In scholarship of gender issues in the Middle East, one can sometimes discern two opposing assumptions. The story of Sasaʿa and the laws of inheritance in Islam are useful tools for those who claim that there was a sharp turn from the immoral, Jahiliyya, to moral Islam, a pivot that included, not only principles of faith, but also new rules of behavior, including respect for women. This position, presents Islam as a real and tangible improvement in the lives of women in the Arabian Peninsula: from lacking status and value, to people, believers, with equal obligations and rights in the eyes of God.

On the other hand, the other position reads the Jahiliyya past differently, and emphasizes a change for the worst, actually. It assumes that during the Jahiliyya women were strong, owned money and property and were involved in society in various ways. Khadijah, the Prophet’s first wife, was a good example of this. whereas Islam pushed women away from positions of influence and prevented them from filling valuable roles in society.

Both positions are apologetic, and both of them use women no less than scholars of yore did. Both use female figures to reinforce their positions, and negate women’s basic agency and define their sphere of activity in the past and in the present for them.

Religious figures, social activists, internet commenters, and more, are party to the historians in this trend. The public discourse that was awakened over the last few weeks in light of the many incidents of violence against women in the Arab sector in Israel, demonstrates this very well: Sasaʿa’s story often stars in the attempt to teach “the right way to behave”, and proper gender power roles in society and in the family are explained and justified in religious terms, with verses from the Quran and traditions attributed to the Prophet.

Permission to use violence against women is derived from verse 34 in the Sura of Women. Many commentators claimed, and still claim, that this verse proves the superiority of man over women and is the foundation of the right of a husband to use violence against his wife. This verse is mentioned again and again in discussions regarding the authority a man has over a woman’s life, the tools with which he is permitted to enact this authority, and the ways that are accessible to women to receive aid in situations in which men take advantage of this right malevolently.

However, this verse, like many other questions regarding the place of women in relationships, family and society, is still up for interpretation. Even as early as the first centuries of Islam, the four legal Islamic schools of law disagreed regarding what are the limits that curb the right of a man to hit his wife: the number of blows, the way in which he may hit her, which results render the hits legitimate or illegitimate, but also, maybe most importantly, the very essence of the permission to strike. How does this verse go hand in hand with the characterization of the Prophet Mohammed as a gentle person, who had respectful relationships with his wives, without any mention of use of violence? Can one see the documented behavior of the Prophet in the sources as proof of the rejection of the right to hit, and any use of violence against women?

In recent years feminist readings of the Quran, which suggest additional interpretations of this verse and other verses and makes room for a gender balance that would allow women to integrate into diverse cultural, economic spheres, in the private arena and also in the public arena, have been added to the discussion.

However, it seems that the legal argument has been too secondary in the public discourse regarding domestic violence. The superiority of men, and the right to use force against women is prioritized over religious law, and those who support this right use claims that fit their stances and ignore the religious legal disagreement on the subject both in the far past and in the present.

Using the Quran in order to justify the right of a man to hit his partner, or to reject that right is part of the discussion regarding the place of women in the private sphere and the public sphere in the 21st century. However, the interpretation of religious law is influenced by accepted social norms in a given place and time, by the laws of the country, and the traditions of the community and family. Recognizing that interpretation is a chosen interpretation and not a clear-cut body of knowledge will make it possible to widen the boundaries of the discourse, and at the same time allow for a reading of the past without the obligation to justify the present, and could even to lead to strong and un-compromising action towards the eradication of violence in society and in the family.