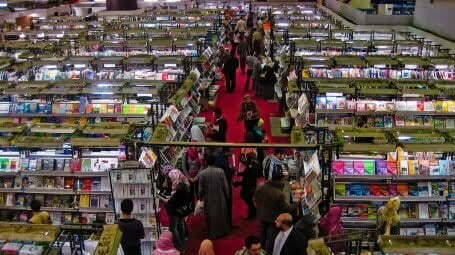

In recent decades, book fairs in the Arab world have become a tradition. Two months ago, the 29th Cairo International Book Fair was held in the Egyptian capital, which hosts every year masses of Egyptians as well as guests, mostly from Arab countries. This year, Algeria was chosen as the honorary guest of the fair. Concurrently to the Egyptian fair, the 24th Casablanca international Book Fair was opened in Morocco, and Egypt was chosen as honorary guest.

These fairs are an extended “Arab Book Week” (the equivalent of “The Hebrew Book Week”) that lasts for ten days or more. But unlike the Israeli version, these are diverse cultural events: a combination of “high culture” and popular culture that includes discussions about literature and art, musical events and film screenings as well as street performances and food stands.

The Arab book fairs also have a political dimension – they are usually sponsored by governments, for which these events are an opportunity to convey messages – national, religious and others – to the public at home or to an external public in the region or elsewhere. Moreover, the book fairs in Arab countries are a unique window for understanding the political and social issues that are on the top of the agendas of these countries, and they provide an opportunity to examine the relations and the balance of power between various countries.

The media discourse of the fairs reflects problems common to all countries in the region: Arab readership is limited due to low literacy rates; significant gap between the Classical Arabic and the spoken Arab dialects, as well as the persistent dominance of foreign languages in some of these countries. Moreover, as elsewhere in the world, changes in reading habits as a result of the spread of content on the Internet and the development of social networks, pose a great challenge for the regional book market.

Many book fairs in the region focus on children and adolescents’ literature, and are held in cooperation with schools under slogans such as “We Are All Readers” or “The Young Reader.” This is evidence to the government’s recognition of the severity of the illiteracy problem, connected to the distress of local education systems.

Many people in the Arab world cannot afford to purchase books. After the eruption of the “Arab Spring” and the general rise in the cost of living and book prices, the problem only intensified. As far as the publishers are concerned, the Arab market is a small one in which the phenomenon of forgery is prevalent. Writers and thinkers branded as regime critics, are the main victims of censorship, and in recent years there has been an increase in the censorship of books under the pretext of “harming the values of the state” or “preaching extremism and ethnic strife”.

Literature affiliated with Sunni political Islam (the Muslim Brotherhood) and the militant Islam (Salafiyya-Jihadiyya), or literature identified with Shi’ite Islam, in particularly sensitive. The latter because it arouses the regime’s fear of Iranian subversion. For example, publications of writers who signed a petition in demand of early presidential elections in Algeria, due to president Bouteflika’s poor health, were disqualified from the 22nd International Book Salon of Algiers. Islamic literature, which was particularly prevalent in the Cairo Book fairs during the Mubarak era, experienced a retreat under President al-Sisi, who instructed Al-Azhar University to promote a moderate (Wasati) version of Islam.

In recent years, Shi’ite books originating in Iran or Lebanon have been banned from Moroccan fairs. On the other hand, the book fair which was recently renewed in Damascus, due to the strengthening of Assad’s regime, was attended by publishers from Iran, as well as Russia. In addition, many Arab countries cultivate culture as one of the means to combat terrorism and religious extremism.

Historically, the oldest and central book fairs in the region were those in Egypt and Lebanon, where the largest and most important publishing houses in the Arab world operate. However, in recent decades and even more so in the wake of the “Arab spring” in 2011, there has been a certain decline in their status, in parallel with the rise of the fairs in the Gulf countries and in the Maghreb countries, which enjoy relative stability. It turns out that both culturally, and not only politically, the Arab center of gravity is moving from the Fertile Crescent to the geographic periphery.

The United Arab Emirates, for example, is an honorary guest at many fairs and holds impressive fairs itself, at very high costs, in the capital Abu Dhabi and in the city of Sharjah. A few years ago, the “Gulf Cooperation Council” was the honorary guest at one of these fairs. On each day of the fair, there was a different show that represented each of the six countries included in the council, a demonstration of the evolving culture of the Gulf region.

The current crisis between the Gulf countries no longer allows the display of such a united front. This was evident at the 28th International Book Fair of Doha, which took place despite the absence of Egypt and despite the siege imposed on Qatar by its neighbors. On the other hand, the non-Arab regional powers that are close allies of Qatar – Turkey and Iran – participated in this fair.

Moreover, the advisor of culture affairs of the Qatari Amir presented the fair as a great success, and declared that culture is not an issue for boycott, and that “literature and the arts should remain above political differences” but it seems that in the Arab world, like everywhere else in the world, it’s impossible to separate culture from politics.

This article is dedicated to the memory of Ayellet Yehiav, an expert for Egypt’s politics, society and culture at the Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Ayellet has taught generations of Middle Eastern scholars to understand Arab politics through culture in general, and literature in particular. We will all miss her, R.I.P.